License Tensions Could Cost IONQ More Than The SKYT Acquisition

IonQ’s acquisition of SkyWater Technology was framed as a strategic move to secure advanced manufacturing capabilities critical to the future of quantum computing. At face value, the logic is straightforward: quantum systems are running into scaling constraints, and deeper control over fabrication could offer a competitive edge. But the implications of the deal extend well beyond quantum—and that is where the tension begins.

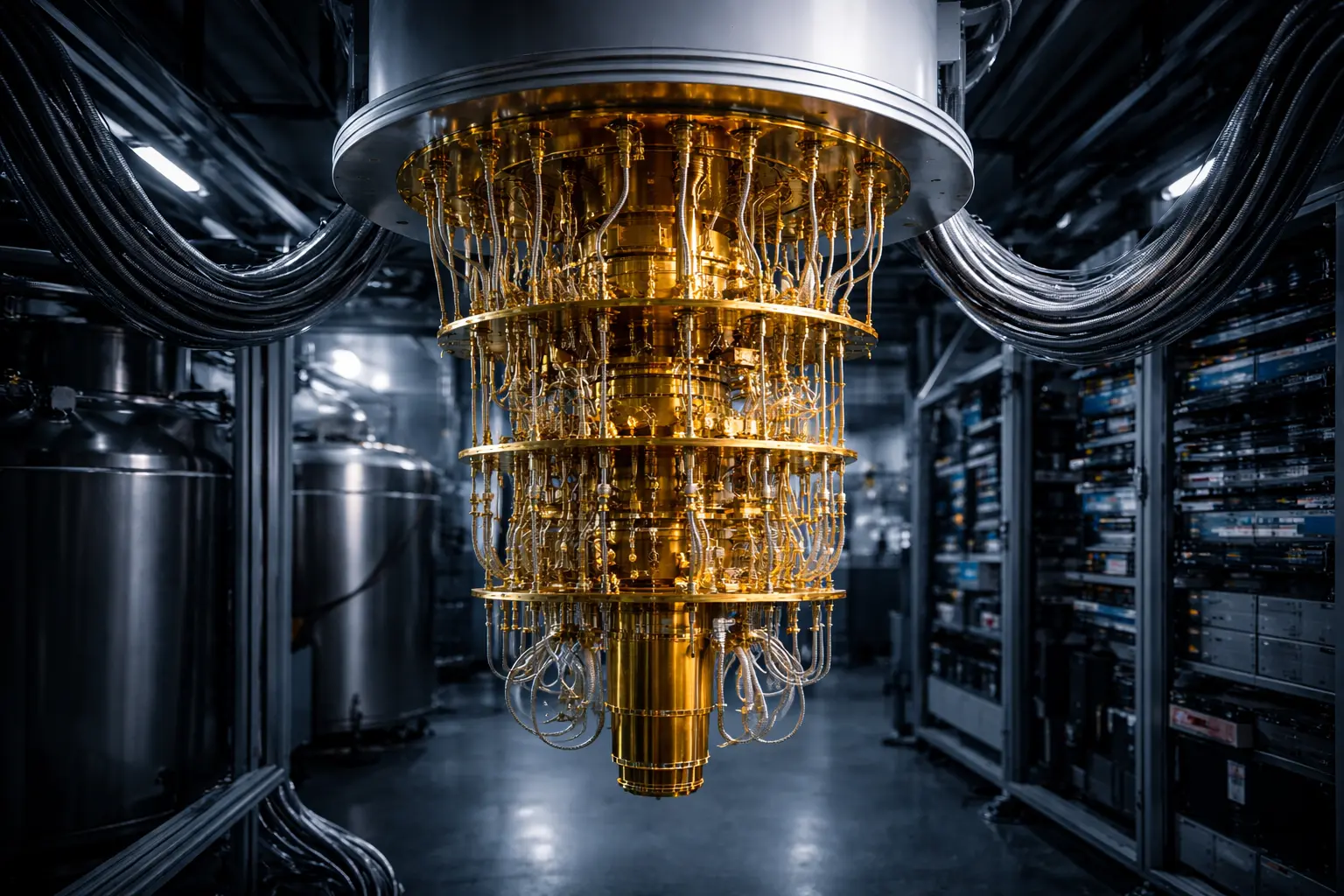

The current computing wall

Quantum computing’s central challenge is no longer theoretical feasibility. It is scaling. As quantum systems grow, performance is increasingly constrained by physical distance, power delivery, and the efficiency of on-chip interconnects in conventional 2D architectures, rather than by qubit design itself. The pattern mirrors a familiar phase in classical computing: progress slows not because the core idea fails, but because the hardware architecture cannot scale efficiently.

This is the wall IonQ and its peers are approaching. Regardless of architecture, quantum platforms require ever-higher integration density, tighter alignment tolerances, and closer coupling between logic, memory, and control. At that point, manufacturing—not quantum theory—becomes the binding constraint. And that reality reframes what IonQ has actually acquired.

Why packaging is not the answer

Confronted with these scaling limits, IonQ could continue extending conventional 2D fabrication, but only through increasingly complex approaches. That pressure typically shifts the industry toward advanced 2.5D packaging, often presented as the natural next step. It is not

Crucially, 2.5D packaging does not eliminate physical distance inside the chip. As systems scale, distance, power delivery, and on-chip interconnect efficiency become the dominant constraints. Packaging can rearrange those limitations at the system level, but it cannot remove them. For quantum systems, where performance is tightly coupled to physical layout and control precision, that distinction matters.

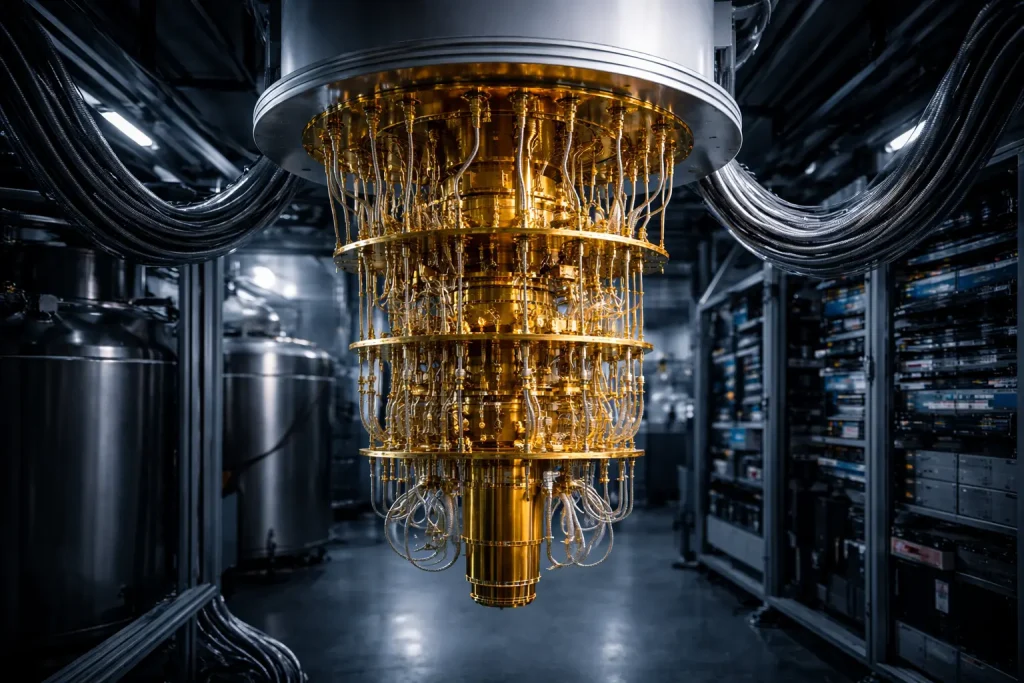

3D monolithic integration: the structural fix

The only path that structurally resolves these limits is true 3D monolithic integration—a manufacturing capability controlled by SkyWater Technology. Unlike 2.5D packaging, which stacks finished chips, 3D monolithic integration fabricates multiple active transistor layers directly on top of one another during the manufacturing process. Logic, memory, and interconnect are built as a single vertical structure, collapsing physical distance inside the chip.

This approach delivers density and efficiency gains that packaging cannot. Interconnect lengths shrink by orders of magnitude. These benefits are structural, not architectural, and they apply regardless of end market.

SKYT’s M3D origins and licensing reality

SkyWater Technology’s role in 3D monolithic integration originates in Stanford-led research, with participation from MIT and funding from the U.S. Department of Defense. This work was not conceived as a bespoke solution for a single application. It was developed as a manufacturing breakthrough with broad commercial relevance across multiple end markets.

Stanford’s technology licensing model reflects that intent. Licenses are structured to enforce real-world deployment, measurable progress, and monetization. Diligence requirements and progress reporting are not formalities; they are core mechanisms Stanford uses to ensure foundational manufacturing technologies achieve broad commercial impact rather than subsidizing a single company’s private advantage.

Within that framework, a commercialization path that frames 3D monolithic integration primarily around a single internal use case—such as quantum computing—creates tension. Narrow application, delayed deployment, or effectively parking the technology inside a long-term internal research program would run counter to how Stanford structures and enforces its licenses, even if specific contractual terms are not publicly visible.

SKYT Fab 25 constraint

That tension is magnified by manufacturing reality. SkyWater’s Fab 25 exposes the structural limits of the IonQ–SkyWater arrangement. The company’s 3D monolithic capability relies on scarce, highly specialized tooling, non-standard process flows, and tightly scheduled capacity, while scaling M3D for commercial deployment requires external customers, long yield-learning cycles, dedicated customer engineering, and sustained capital investment. Quantum fabrication follows a different logic entirely: low-volume, bespoke runs, specialized talent, distinct yield metrics, and a research-driven cadence. In practice, these are conflicting operations inside the same fab—running one well makes it harder to run the other efficiently.

IonQ’s framing problem

IonQ has publicly stated its intention to use SkyWater’s 3D monolithic technology to advance its quantum computing roadmap. That framing matters. In IonQ’s communications, the emphasis has been on quantum-specific application, with little to no discussion of market-agnostic deployment, external customer access, or aggressive commercialization beyond quantum systems.

The absence is notable. When foundational manufacturing technologies are discussed solely through the lens of one internal use case, it raises questions about scope and intent. For a technology licensed under expectations of broad commercial impact, narrow framing is not neutral. It is a signal.

Independence vs oversight: the tension

To IonQ’s benefit, it has stated that SkyWater will continue to operate independently, albeit under IonQ’s oversight. The ambiguity lies in how far that oversight extends. If oversight constrains SkyWater’s ability to pursue market-agnostic customers or to commercialize 3D monolithic integration aggressively across industries, friction with licensing expectations becomes inevitable. Independence in name does not resolve this tension if strategic control limits execution.

The valuation inversion investors are missing

At the core of this tension, manufacturing constraints and licensing pressure invert the financial logic of the deal. Many investors view SkyWater’s technology as a strategic upside for IonQ. That framing is backwards. The more relevant question is whether IonQ can serve as a stabilizing structure that enables SkyWater to meet its licensing obligations and realize its commercialization potential.

If SkyWater’s 3D monolithic technology is constrained by IonQ’s strategic focus, it becomes a liability rather than an asset. In that scenario, the burden flows upward. IonQ must absorb the cost of maintaining a commercially aggressive manufacturing platform while pursuing a quantum timeline that may not align with licensing pressure.

Closing warning

This relationship will not be defined by quantum milestones alone. It will be defined by commercialization behavior. The path SkyWater takes with 3D monolithic integration—who can access it, how broadly it is deployed, and how aggressively it is monetized—will determine whether the partnership is coherent or conflicted.

Investors should watch actions, not assurances. In deals involving foundational manufacturing technology, licensing intent is not a footnote. It is the constraint that ultimately determines whether strategic alignment exists—or whether the structure collapses under its own contradictions.

Disclosure: This article reflects the author’s personal analysis and opinions and does not constitute investment advice. The author does not hold shares in IonQ, Inc. at the time of writing. Images used are independent illustrative renderings and are not official IonQ, Inc. promotional materials.